I couldn’t wait to see China for the first time. I so wanted to meet the economic tiger that might pin down the US, which for now is still holding all the cards. My observation area encompassed technological startups in Shanghai and Hangzhou.

All I knew about Shanghai was the standard vision by a man from the west: the most populated Chinese city, a mighty financial and economic centre; the third biggest port in the world, glass skyscrapers, refined colonial architecture and old sanctuaries. “Picturesque” poverty and enormous wealth. Friendly, hard-working people, who value family bonds above enrichment. But it was still at the airport that I had to verify my idea of the Middle Kingdom.

To start with, head of the German Economic Chamber in Shanghai, Simone Pohl, immediately made us realise the enormous ambitions of the Chinese leaders. “They say the growth of Shanghai is a reflection of the development of entire China. By the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China, that is by 2049, the country plans to become an economic superpower. They want to change the positioning of their products and the meaning of the information they carry. “Made in China” is to symbolise not only products that are easily available, but also very good. And most importantly – China wants to become a leader in the use of artificial intelligence,” says Simone Pohl.

“Can this all be done?” – thought I, remembering the queue waiting to be interviewed by the guard at the airport, where on one side they were playing a patriotic video building pride of being Chinese, and on the other side another video about how the police uses data about citizens to provide them with security (digital identification systems are China’s specialite de la maison). In our world we call it surveillance, or more euphemistically – violation of personal freedom. But the Chinese believe it is a sign of progress, which helps build the capital of public confidence.

During my week-long stay in Shanghai, as I was visiting such technological powers as Alibaba, musical.ly or mobike, I often heard that the Chinese are hungry for success. Is it only a linguistic expression?

Apparently not, as the Chinese employment market is now being flooded by a generation whose parents knew what real hunger was. In a society of one billion three hundred ninety one million people (all the Poles times 36) these are not isolated stories. It is a generation which is the consequence of the “one family – one child” policy. This means one person usually works for two parents and four grandparents. These people are very, very hungry for success. The methods they use are congruent with the idea of a career in the Western world.

Looking at what China does globally, we should filter it with two words: money and pragmatism, because the measure of success in China is money. In order to be successful, Chinese people are brutally pragmatic.

They don’t discuss with “our” world about values, because their world has always been – since the times of the empire till now – founded in paternalistic authoritarianism, which in turn is based on the Confucian values. Young Chinese, educated at the best western universities, talk with us in the language of business that we love so much. They emphasise that they increase their economic impact globally due to implementing their culture of work in business.

Tom Xiang, owner of Move Shanghai startup, co-author of a very popular podcast about the influence of Chinese technology on the entire world, is frank about it: “If you admire what Alibaba does, don’t forget that they are gangsters. All they care about is money.” Somebody asked: “Can we quote your opinion?” “Of course, I often talk about it,” Tom replied.

No matter what we think about it, Alibaba is not only Chinese e-commerce giant (equivalent of Amazon), but also more than 30 technology companies which use and test learning algorithms, that is artificial intelligence (AI). The founder of the company, Jack Ma, has found the golden key to success. This entrepreneur loved by Chinese people plays the role of a contemporary hero – just like Steve Jobs in our cultural circle. Jack Ma is consequently building his position; for instance, he played in a film where he was, naturally, a positive character. His story is told by the Alibaba Museum, and Jack himself inspires crowds. He is a living proof that it is worth making an effort – and he talks about it often and with eagerness.

It seems Jack Ma has also a sense of humour, if we look at the name of his company. Ali Baba is the protagonist of one of the most well known tales from the One Thousand and One Nights collection, who became rich after he found the magic words opening the gate to a cave. Of course, this is just a blink to the audience, because instead of saying “Open sesame” Jack Ma is systematically building the power of his company. We spent an entire day in Alibaba, and this was the most impactful experience. The company, which started as a purchase platform between Chinese and western companies, today – in addition to improving and creating new quality in logistics – is first of all a technological power, exploring the possibilities of learning algorithms, changing the face of purchase making or hotel booking.

Chinese often say that when they enter western markets, they feel as if they were taking away toys from children… Was this what the businessmen were thinking who first invested in vitamin C production plants in the west, then took them over and shut them down, only to shift 95% of vitamin C production to China? Naturally, the prices went up accordingly.

Today, the Chinese are investing in the best real estates in Barcelona and Paris, not to mention docks in Greece. Tuition fees at the best universities, like Oxford or Harvard, are staggering, because they are dictated by Chinese customers, who are ready to pay in cash. The vision of 400 million people who are now making a pile, traveling across Europe like it’s a Disneyland, does not seem so far away.

The X generation can remember that in order to achieve something – you had to work hard. But this memory is coming to an end. A new generation has arisen, who wants to work with passion and for pleasure. They don’t want to live to work, they want to work to live. Meanwhile in China, working for 12 hours a day minimum for six days a week is a norm. When the Chinese spend 14-16 hours working on a project, they will talk about it with excitement and pride. They will not complain. They won’t mention depression or burnout. If they decide to leave from work, they say it is because they want to spend more time with their family. The suicidal statistics (ca. 300 thousand people annually) – so alarming for people in the West – are taken with Confucian calmness in China.

In China, where the state has always been most important, there is no sense of individuality, no need for freedom. Any attempts to transplant the western model of employee engagement, with ability to make decisions individually, would surely fail. Chinese employees expect clear guidelines from the employer – the boss should know what to do, and they should perform the task the best they can. In Alibaba one project is simultaneously developed by 16 teams. The competition is harsh; the team with the best result is the winner.

Nothing is impossible for the Chinese, everything is achievable. But everyone must be prepared that it’s going to be hard, and that’s from early years. There is an expression describing Chinese parents with excessive ambitions regarding their child: “They want their child to be a dragon.” It seems such attitude is not rare. Chinese children are brought up believing that they must be the best, because if you don’t win – you die. To our European suggestions regarding happy childhood, and that there’s no need for three years old to be able to count to 200, Chinese parents respond with calmness: “They don’t need to at your place, because there is no competition.”

I want to say goodbye to Shanghai by taking the subway to the airport. But first, the last meal, the last yuans spent, and suddenly a thought crosses my mind: can you pay via card in the subway? I Google it and… no, you can’t. I’m in the centre of the city, so it seems it should be easy to find an ATM. Google and maps.me (the apps I had on my phone) point to three locations, but the information turns out no longer current. At last, in one of the hotels a nice lady tells me in broken English where I can find an ATM – luckily, it is a way to an old temple that I already knew. Phew, equipped with cash I was able to buy a ticket.

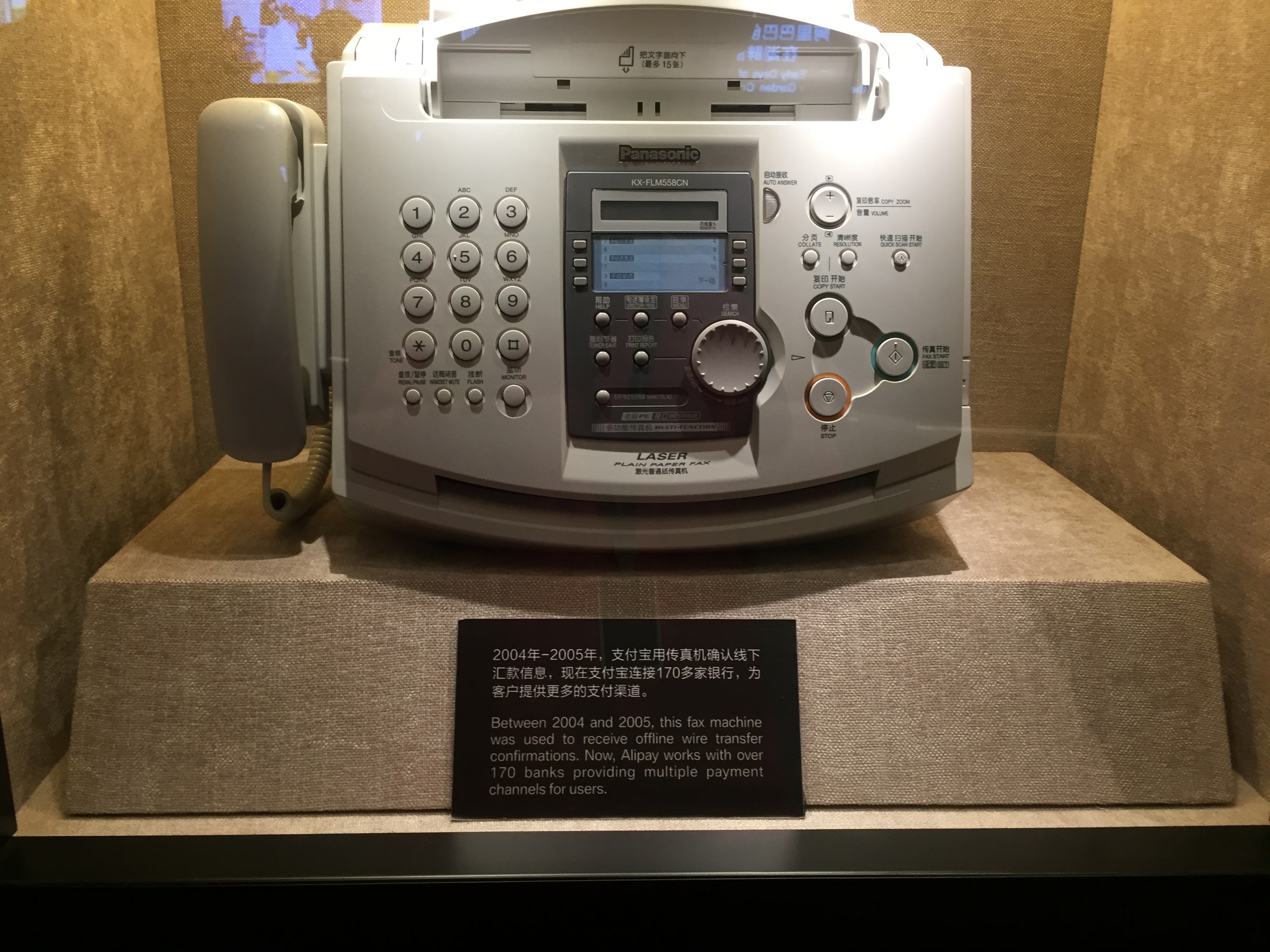

Is China so back behind with their payment system that they’re not using cards? No, it is us who is back behind them, as they omitted the card stage and most payments are made via phones. The most popular payment apps are alipay and wechatpay. The telephone is also irreplaceable when a Chinese wants to get a loan fast. It’s enough to ask for it via an application, and within a few seconds there comes the decision about how much money the person can get. Two more seconds and the money is available.

What about cards? It’s possible to pay with them, but mostly in places which offer services at prices for western tourists.

While in Shanghai, we also visited Tezign company, an app in which the computer analyses the customer’s needs and selects the best supplier. As for now, due to ethical reasons, computers are not creating the products themselves, but there already exist ones that are good at graphic designing, not to mention music creation.

In the city of technological revolution, every step I took I was asking myself: How is our service market changing? What do we have to offer to the Chinese? Can we be partners?

In order to understand the Chinese way of thinking, I started to learn Mandardin with my daughters. In our first class I realised why the Chinese – contrary to Polish people – do not like to complain. Why? Because complaining makes you feel worse and has a negative influence on your health. So why do it? – as Phibi, my Chinese Teacher, explained to me. “We Chinese love to develop, and complaining about something you are not able to change makes no sense.” My daughter Marysia summarised with appreciation: “They’re clever – we can learn a lot from them.”

Read more about China on contentic

Still hungry for Shanghai? Here’s a link to stories by other participants of the trip: Knut Nicholas Krause - New Trends come from China - Bike Sharing - and What Media Companies Can Learn from Chinese Startups Michael Oschmann - From #FOMO to #FOBBO, our trip to China 2018 Pierre Samaties - Digital China - a #NewWorldOrder

Kategorie: power of contentic